Long before the advent of cinema and television, a fascinating array of optical toys captivated audiences and laid the groundwork for modern visual media. These ingenious devices, spanning centuries, harnessed the principles of optics and perception to create moving images and three-dimensional illusions, offering a glimpse into distant lands and fantastical worlds. From simple spinning discs to sophisticated stereoscopic viewers, these seemingly simple playthings were instrumental in our understanding of visual perception and the evolution of entertainment technology.This exploration delves into the rich history of these optical wonders, tracing their development from the 17th century to the mid-20th century. We’ll examine the innovative designs and scientific principles behind iconic toys such as the magic lantern, thaumatrope, phenakistoscope, zoetrope, praxinoscope, stereoscope, and the enduring View-Master. Discover how these early forms of animation and 3D imagery not only entertained generations but also profoundly influenced the technological advancements that shaped our modern visual landscape.

Read more: Top 5 Learning Resources for Kids' Optics

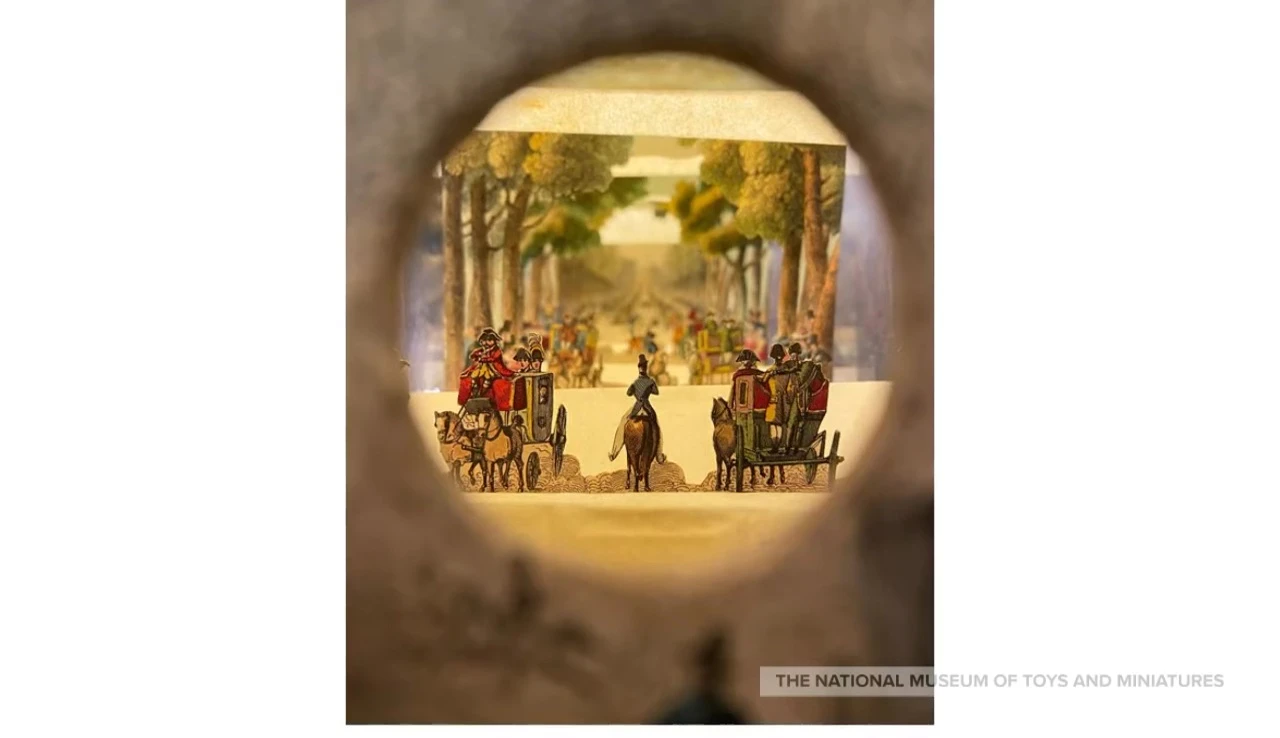

Tunnel Books: A Window to the World

Tunnel books, dating back to the 1600s, offered a unique glimpse into distant lands for people with limited travel opportunities. These ingenious creations used multiple layers of paper folded accordion-style to create three-dimensional scenes.

The layered images, when viewed through the tunnel, created a sense of depth and perspective, making faraway places feel surprisingly tangible. They cleverly employed the principle of perspective to transform flat images into a three-dimensional experience.

Magic Lanterns: The Dawn of Projected Images

Magic lanterns, invented in the 1600s, predated modern film and television. Initially illuminated by candles, later by gaslight, these devices projected painted glass slides onto a wall or screen.

These projected images, often depicting travel scenes or storytelling, captivated audiences. Their popularity soared in the 19th century, with shows held in various venues, from theaters to homes, making them a widespread form of entertainment.

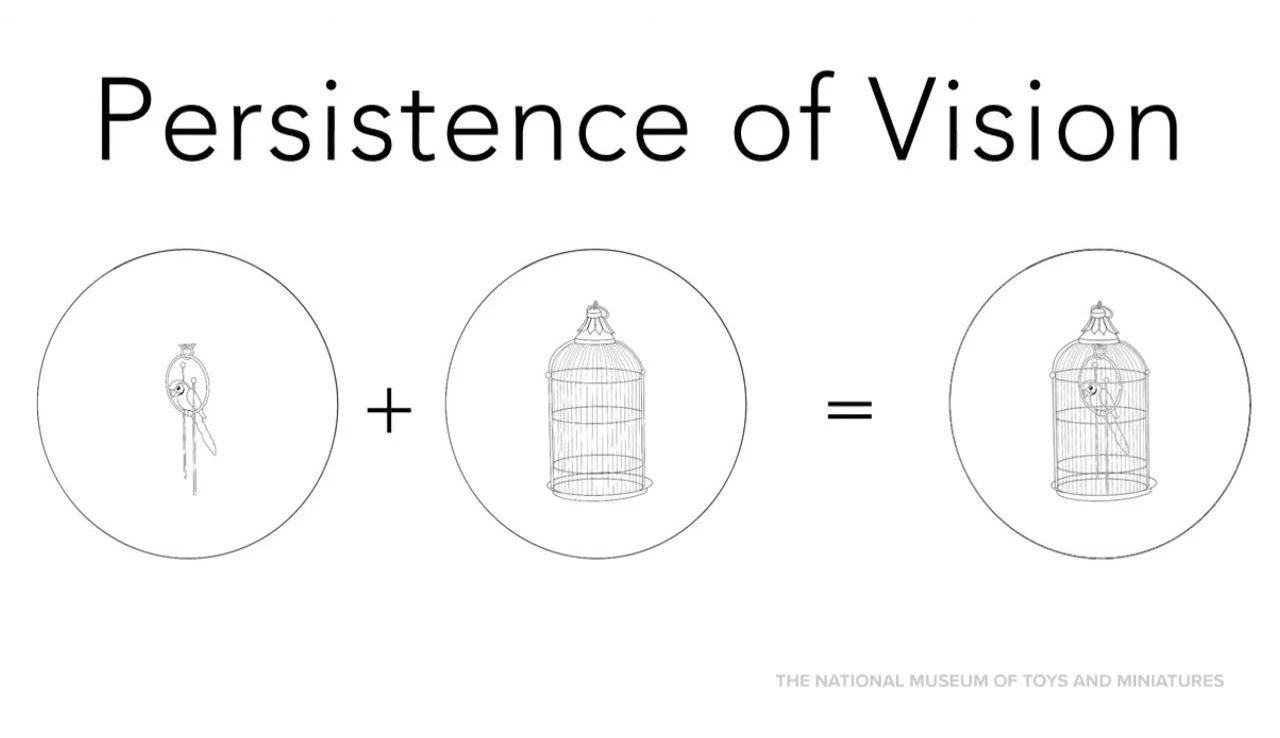

Thaumatropes and Persistence of Vision

Thaumatropes, meaning 'wonder turner' in Greek, are simple yet fascinating devices that leverage the persistence of vision. By rapidly spinning a disc with two different images on each side, the images appear to blend into one.

This optical illusion is a direct result of the eye's tendency to retain an image for a brief moment after it disappears. The rapid succession of images fools the brain into perceiving a single, combined image.

Phenakistoscopes and Zoetropes: Early Animation

Both phenakistoscopes ('deceptive viewer') and zoetropes ('wheel of life') utilize persistence of vision to create moving images. The phenakistoscope, invented in 1832, involves spinning a disc with a series of images and viewing the reflection in a mirror.

The zoetrope, also invented in 1832, uses a slotted cylinder containing a strip of images. As the cylinder spins, viewers look through the slots to see the animation. Both devices represent early forms of animation technology.

Praxinoscopes and Stereoscopes: Enhanced Viewing Experiences

The praxinoscope, invented in 1877, improved upon the zoetrope's design. Instead of slits, it used a circle of mirrors to create a brighter, clearer image, enhancing the viewing experience.

Stereoscopes, incredibly popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, presented viewers with three-dimensional images using two slightly different pictures of the same scene. This mimics how our eyes perceive depth, creating a realistic 3D effect.

View-Masters: A Modern Stereoscopic Legacy

The View-Master, a modern iteration of the stereoscope, also utilizes the principle of binocular vision to create 3D images. Originally marketed to adults interested in nature scenes, its popularity expanded to children in 1951.

Surprisingly, during World War II, View-Masters even served as training tools for military personnel. Their versatility and enduring appeal have secured their place in the history of optical toys.

Conclusion: The Enduring Impact of Optical Toys

Optical toys, despite their seemingly simple designs, played a crucial role in the development of modern visual media. Their use of scientific principles like persistence of vision laid the groundwork for the technologies we enjoy today.

From simple spinning discs to sophisticated stereoscopes, these toys not only entertained but also educated, inspiring wonder and curiosity about the world around us. They offer a fascinating look into our visual heritage and the evolution of entertainment.